7.

Discussing the production as a whole – it’s a dialogue, not a debate

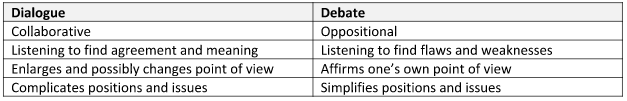

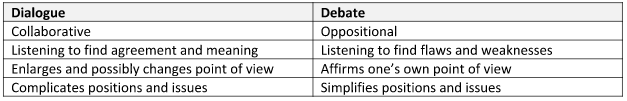

It is only after we have defined (and agreed upon) what it is that we are talking about, that we can rationally discuss the program as a whole. However, the way we talk about it influences the way we think about it. For this reason, it is important that we use dialogue in our use of IAN, and not debate.

Dialogue vs. Debate

This aspect creates an essential role for the moderator. It is

important that the moderator does not participate in the discussion, but

instead, guide it with well-chosen questions:

- What is best about this program? Where does it function well? How? Why?

- How does the program function artistically and communicatively as a whole?

- How does the program function over time? Where is the overall form most functional?

- How is the concerts’ dramatic form built up?

- If the content of the program is familiar to the children: Is the music so available that it can exist without extra help?

- If the content of the program is unfamiliar to the children: What

needs to be done in order to “make contact” between the music and the

children’s perception of the music?

- Which devices are used to facilitate the music? Do these devices function effectively? Are they too little? Are they too much?

- Where do these devices strengthen the program by giving the

children better access to the musical experience? Where do these devices

detract from the musical experience by taking on a disproportional

interest or value of their own?

All participants in the evaluation Dialogue must themselves be

held to a certain level of expectation. Statements cannot be simply

taken as fact, but must be defined and defended. Broad generalities

should not be allowed, only specific, detailed feedback. Strengths in

the program should be explained and exemplified. Specific strategies

should be suggested when weaknesses are identified. It is the

moderator’s job to challenge all unsubstantiated statements.

P: I thought this was a really good concert.

M: Why?

P: Well, the musicians played very well.

M: What particularly impressed you about

their performance, and what context defines “good playing” in this

particular musical style?

P: They had a great deal of technique and played well stylistically.

M: How important is technique and style in this particular concert situation?

P: I’m sure the children can hear and

appreciate this kind of virtuosity, but I am unsure if they have enough

experience with musical style for it to make an impression on them

.

M: If we try to look at the concert from

the children’s perspective, what would seem to be most accessible or

most important to them?

The moderator has a crucial role. He should strive to interrupt

the conversation as little as possible, but quickly step in when it

loses focus or becomes off-topic. The moderator should use questions to

clarify basic information or viewpoints, build upon important themes,

and refocus the discussion as needed. In this aspect, the methodology

for the discussion of the program as a whole uses a type of “question

driven” Socratic Dialogue – a methodology within a methodology.

Leave a Comment